What are fragrances and their effects on health?

Fragrances are mixtures of several chemicals intended to produce a particular scent. Fragrances are used in thousands of consumer products, including but not limited to perfumes, soap, cleaning products, air fresheners, laundry products, personal care products etc. (Caress & Steinemann, 2009). Up to 4,000 ingredients are used in manufacturing fragrances (IFRA, 2011). A single synthetic perfume may contain up to 500 ingredients, 95% of which are petroleum-based volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that easily evaporate and disperse into the air we breathe (MNT, 2008). There is no regulation requiring the manufacturer to disclose specific chemicals used to create the fragrances in their products, as this is considered proprietary information.

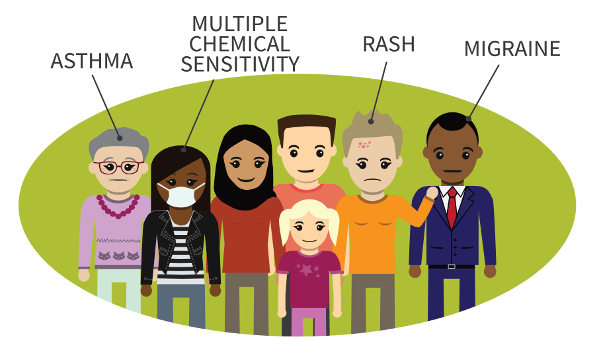

We all inhale chemical fragrances used in almost every consumer product, on a daily basis. Many of these products are toxic and have harmful health effects, as evidenced by several studies (Rastogi, et al., 2001; Temesvári, et al., 2002). For instance, high levels of phthalate esters are used to maintain the longevity of scent in numerous perfumes, even though phthalate esters are known endocrine disrupters (Al-Saleh, et al., 2017). Chemical analysis has revealed some ingredients to be carcinogens, developmental toxins, or neurotoxicants. Several ingredients used to produce fragrances exacerbate or may cause many health conditions such as asthma, eczema, multiple chemical sensitivity, sinus problems and migraine headaches.

Approximately one-third of Canadians experience symptoms when exposed to perfumes, fragrances and other scented products (Sears, 2007; Steinemann, 2018). Considering the diversity of chemical products and the specific ways each individual reacts, widely varying symptoms can be expected from exposure to scented products. Infants can experience severe symptoms such as diarrhea, vomiting, or earache, and possibly cough or cold, fever, wheezing, breathlessness, and rashes (Farrow et al., 2003). In adults, symptoms are extensive and vary from one individual to another. Symptoms triggered by exposure to fragrances can encompass headaches, dizziness, difficulty concentrating, feeling dull, groggy or spacey, fatigue, watery eyes, runny, stuffy nose and sinuses, wheezing and shortness of breath, or rashes (Caress & Steinemann, 2009; Elberling et al., 2005; Silva-Néto et al., 2014; Uter et al., 2013).

Fragrance-free policies in health-care facilities

With increasing awareness of the adverse health effects of fragrances, many health-care facilities around the world are becoming fragrance-free. Policies have been implemented in several government and hospital facilities in Canada where visitors, patients, health-care professionals, and other staff members are asked to refrain from using any products containing fragrances.

Products containing fragrance may be deodorants, hairsprays, shampoos, conditioners, soap, aftershaves, perfumes, colognes, cleaning products, etc. Establishing fragrance-free environments is not a new culture. It is well-established in Ontario, Nova Scotia, Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, the Yukon and the Northwest Territories.

Most of our time is spent indoors where the air quality can be two to five times more polluted than outdoor air (Environmental Protection Agency-EPA, 1987). Fragrances being one of the most prevalent indoor air pollutants, indoor air quality should be kept free of any of these hazardous substances.

It is equally important that health care facilities in Québec implement fragrance-free policies to accommodate sick and vulnerable populations. No patient goes to a hospital or health-care practitioner expecting to be made sicker. No health-care worker would deliberately do anything to harm patients, colleagues and, potentially, themselves. But when health-care workers choose to apply products containing fragrance to their skin, hair or clothing, they may in fact be doing just that. One has a choice whether or not to wear perfume. The person who reacts to fragrances has no choice or warning when exposed. These products are used for social pleasure. However, those who react suffer social isolation. Access to basic services becomes difficult or impossible for these people. Cardio-respiratory patients can be made critically ill by unexpected exposure to fragrances.

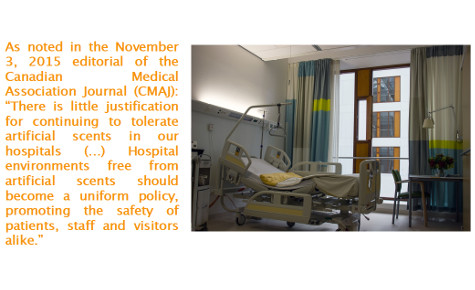

As noted in the November 3, 2015 editorial of the Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ): "There are many practices that are acceptable outside hospitals — but not inside. One of these is the application of artificial scents to our bodies (…) There is little justification for continuing to tolerate artificial scents in our hospitals (…) Hospital environments free from artificial scents should become uniform policy, promoting the safety of patients, staff and visitors alike."

Asthmagens, substances within fragrances that provoke asthma or trigger asthma attacks, are of particular concern to hospital staff. Hospitals show the highest reported rate of occupational asthma (Pechter, et al., 2005). As stated by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in their scent free policy: "Fragrance is not appropriate for a professional work environment, and the use of some products with fragrance may be detrimental to the health of workers with chemical sensitivities, allergies, asthma, and chronic headaches/migraines."

Healthcare facilities should be a secure shelter for people who are ill; a go-to place without any second thought other than to be treated. The hospital environment should accommodate all patients regardless of their specific illness. Patients’health and well-being should be the top priority.

Therefore, all products containing fragrances, including cleaning products, need to be eliminated from the healthcare spaces. We strongly argue that fragrances have no place in a health-care setting and that good quality, fragrance-free air is a basic human right. We therefore urge all health-care workers and hospitals across Québec to become fragrance-free in accordance with the basic right to clean air.

This webpage is meant to assist you in raising awareness and encouraging the development of a fragrance-free policy in your health-care facility. Even though the task may seem daunting, there are effective ways a health-care facility can succeed, especially through learning from other hospitals that have successfully implemented such policies.